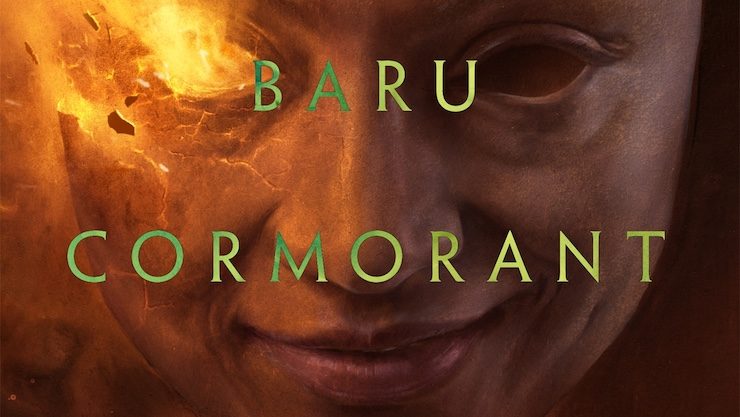

Baru Cormorant hasn’t always been a traitor, and she hasn’t always been a monster. In another life, she is an islander and a prodigy, a lover and a daughter. She is a subject and a citizen, or something in between. When the empire of the Masquerade invades and seduces her home, Baru is reduced to her heritage, even as her opportunities and worldview expand. She is torn between a multitude of selves, some faithful and some masked, but none of them untrue. This is the stuff of empire: not just to unmake a people, but to remake them.

Seth Dickinson’s Masquerade series doesn’t explain our political moment, nor is it a metaphor for 20th century fascism. It instead approaches a much earlier form of despotism, rooted mostly in 19th century imperialism and Enlightenment science. Dickinson deftly rearranges these historical elements into a thrilling second-world fantasy series, taking them away from the realm of allegory and allowing the story to weave new interpretations into old ideologies. The Masquerade has received accolades from reviewers for its world-building, diversity, brutal consequences, and compelling characters, and all of this is right and true. But I’d like to address the elephant in the room.

The elephant is politics. Specifically, our politics.

The Masquerade series presents politics like this: the Masquerade invades Baru Cormorant’s homeland of Taranoke, not through military intervention but through what seems like the natural progression of trade and exchange. When Baru reaches the inner circle of the Masquerade’s cryptarchs, she learns a great many lessons about the mechanisms of empire, among them the use of eugenics and plague to conquer “lesser” civilizations. She has set out to destroy the government that maimed her homeland and that threatens to lobotomize her for sexual deviance, but the consequences of that quest aren’t apparent until The Traitor Baru Cormorant’s end. It takes a rebellion, unconquerable grief, and self-doubt for Baru to learn a secondary lesson about empire: that it is not a kingdom; it cannot be toppled by killing a figurehead or parliament, or even a single nation. Empire makes you a citizen. Empire is a part of you.

When I first read The Traitor Baru Cormorant in early 2017, it wasn’t the only “timely” book on my to-read pile—I reviewed Lara Donnelly’s Amberlough back when the wounds of 2016 were still fresh, and even then mentioned the likes of Star Wars and other pseudo-fascist sci-fi/fantasy-scapes where audiences could think through the horrors of oppression and totalitarian rule in a safer environment, governed by rules of narrative. Reading Octavia Butler’s Parables series was a particularly harrowing endeavor, through a combination of literal “make America great again” slogans (the series was written in 1993-1998) and Butler’s signature ability to make even hope feel bleak. I didn’t expect to find answers or explanations in these stories, or in the various non-fiction I devoured in those first two years (Hannah Arendt and James Baldwin among them), but I did seek context. Traitor was one of the only pieces of fiction that I felt provided that context—not just showing oppression but analyzing the roundabout ways that oppression is born and justified. Reading the recently released Monster Baru Cormorant has only confirmed that feeling.

A huge part of that is, I think, that much of The Masquerade’s inspiration comes from an earlier era. So many critiques of our current politics are rooted in the horrors of 20th century nationalism: the destruction of the other by way of camps, breeding, and mass extinction. But those horrors, even, were a consequence rather than a starting point. Nationalism was born prior to that, and came of age in the 1800s, with all its genocide and state-sponsored violence waiting on the eves of revolution and republicanism. Nationalism was once a tool against despots, used by early capitalists and socialists alike to invoke a base, a collective identity of citizenry where there had been none before. The French revolutionaries, for instance, spent the decades following 1789 attempting to convince their own people, still mostly devout monarchists and Catholics, of the tenets of democracy (often through civil war, and, more iconically, the guillotine) while simultaneously using it as an excuse to colonize and brutalize the known world. When Americans—of the “alt-right” and otherwise—invoke its name, they are often trying to claim some mystical tie to the revolutionaries of 1776, forgetting that at the heart of the revolution was the creation of the nation-state out of a monarchy, the citizen out of a subject—these were not natural, they were not primordial or ahistorical, but NEW and manifested through a century of war and slavery and colonization and blood. Don’t get me wrong: self-described nationalists are often invoking fascism as well. But the rewriting of the historical “West” is all part in parcel of the same narrative.

Buy the Book

The Monster Baru Cormorant

The power of Baru’s story—beyond the, y’know, queer protagonist and riveting story beats—is that it electrifies all of those aspects of our own 19th century into a fantastical Frankenstein’s monster of early capitalism, misused science, and fear of the other (consequently, also a decent description of the original Frankenstein). Baru herself spends the entirety of the second book literally torn asunder, blind and half-paralyzed on one side, as she tries to kill her own regrets and grief. If Traitor is about literal economic world-building, Monster is about identity-building. The Masquerade creates in Baru and its other citizens new selves—from republican to protégé to traitor—where there had been none before. Baru has so many names by the end of the book, even she can’t seem to keep track. After all, nationalism does not bring out something inherent, but creates loyalties and identities and turns them to political means.

Monster does, as Niall Alexander says in his Tor.com review, go a bit off the rails in its first half. I would nonetheless close this essay by encouraging people to read it anyway. Read them both, read them all. No matter how the Masquerade ends, its revelation of the faces of our historical past and of our present selves will be more than worthy.

Em Nordling reads, writes, and manages research in Louisville, KY. In another life, they studied crowds and identity in 19th century Europe.